In 1981 I was 12 years old and in the 6th grade. I don’t remember the specifics of the school assignment, but what I do remember is that I chose the topic and then spent many late nights lying in bed reading about the Salem Witch Trials. I was spellbound. As a young girl growing up in New England it is not too difficult to understand why I was so fascinated with the infamous witch trials that had happened barely 60 miles from where I lived. The culmination of all this reading was a written report. While I had been reading for weeks, like a typical 12 year old, I didn’t sit down to write my paper until the night before it was due. I have vivid memories of sitting at my kitchen table, pecking away at my manual typewriter (because that was the days before personal computers) half the night.

As tired as I was after that long night, in all of my school years I don’t think I was ever so engrossed, engaged, and PROUD of an assignment as I was of that report. I don’t remember the class it was for (social studies, probably?) and I don’t even remember the teacher, but I do remember that I got an A on that report. And it was the start of what has been a lifelong interest in the Salem Witch Trials of 1692. Since then, I have visited Salem several times, watched countless documentaries, and have read a number of books. But it wasn’t until recent years that I was able to explain my fascination as being that of a descendant of people who had played important roles in the trials. Some sort of genetic memory? Perhaps.

Rev. John Hale Farm, 39 Hale Street, Beverly, Massachusetts

By Elizabeth B. Thomsen – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=59095629

My most recent visit to Salem was with a good friend in 2015, along with his father, and daughter, all of who are themselves many-times-great grandchildren of Reverend John Hale. Reverend Hale was the puritan pastor for Beverly, Massachusetts (next door to Salem) who had played a prominent role in the 1692 Witch Trials, initially supporting them but eventually changing his mind and becoming a critic. The group of us arranged for a tour of the historic home that Reverend Hale had lived in then visited several of the museums in Salem before rounding out the day with a visit to the dramatic memorial to the 20 victims of the trials who had been executed.

Before that visit, I had identified a number of ancestors who had likely been present for those trials and several who had played their own tragic roles. William Brown (born 24 Dec 1622 in Salisbury, England and died 24 Aug 1706 in Salisbury, Massachusetts) was one of them. My 11th great-grandfather on my paternal side (through the DeRochemont, Adams, and Hoyt families), William was married to Elizabeth Murford (also my 11th great-grandmother born 1620 in Salisbury, England and died 1692 in Salisbury, Massachusetts). Sadly, Elizabeth was afflicted with some sort of mental illness for several decades prior to the 1692 trials. Mental illness was not well understood in those times.

In 1692, William seized the opportunity to blame his wife’s disorder on witchery and testified against Susannah Martin, claiming that she had bewitched his wife during an encounter several decades before. According to the testimony of William Brown during the trial of Susanna Martin had bewitched Elizabeth in 1660. Elizabeth, “being a very rational woman and sober, and one that feared God, as was well known to all that knew her… did there meet with Susanna Martin, the then-wife of George Martin, of Amesbury.” Just as they came together the said “Susanna Martin vanished away out of her sight, which put Elizabeth into a great fright; after which time Martin did many times appear to Elizabeth at her house and did much trouble her in many of her occasions”; and “this continued until about February following, and then, when she did come, it was as birds pecking her legs or prickling her with the motion of their wings; and then it would rise up into her stomach, with pricking pain, as nails and pins; of which she did bitterly complain and cry out like a woman in travail; and after that it would rise up to her throat in a bunch like a pullet’s egg…”

In April of 1661, during the first trial of Susannah Martin for witchcraft, Elizabeth and Goodwife Osgood were summoned “to give their evidences concerning the said Martin…before the grand jury.” Elizabeth Brown told her husband that Susanna Martin said “she would make her the miserablest creature for defaming her name at the court.” While Susannah was cleared of those charges in 1661, during the 1692 trials when she had been charged once again, William Brown testified that from that encounter in 1661, “to this very day (30 years or more) she [Elizabeth] has been under a strange kind of distemper and frenzy, incapable of any rational action, though strong and healthy of body.”

In spite of all the testimony against her, Susannah maintained her innocence, stating that “I have led a most virtuous and holy life.” Tragically, based on the testimony of William and some other evidence, Susanna Martin, a mother of 8 and a widow, was convicted on June 29 and executed by hanging on July 19.

Knowing this story during my latest visit to Salem, I somberly visited Susannah Martin’s memorial and quietly asked for her forgiveness.

I had also identified other connections to the Salem Witch Trials, such as John Alden (the son of John Alden and Priscilla Mullins, Mayflower passengers and my 11th great grandparents) who had been accused of witchcraft, but fled and hid until the mania was over, The same was true of Dudley Bradstreet (son of Simon Bradstreet and Anne Dudley my 11th great grandparents).

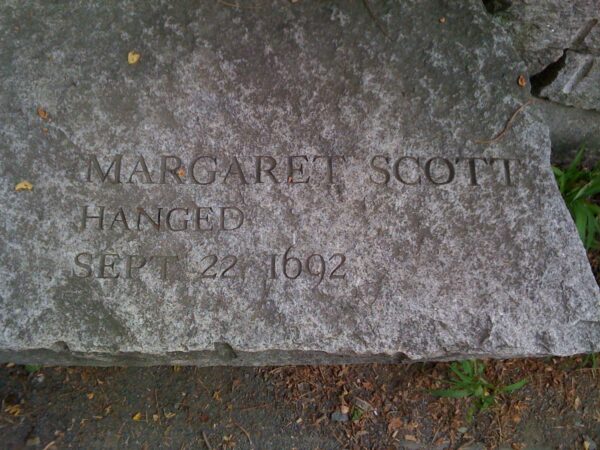

But it wasn’t until this year, 40 years after that 6th-grade report, that I found the connection that made it all fall into place for me, and finally justified my fascination. Margaret (Stephenson) Scott, born in 1616 and my 11x great grandmother through my maternal line, was among the last group of eight souls found guilty of witchcraft and executed by hanging on 22 September 1692. Hanged with her were Mary Eastey, Martha Corey, Ann Pudeator, Samuel Wardwell, Mary Parker, Alice Parker, and Wilmot Redd.

As a member of the lower class, very little is known about Margaret Stephenson. She was born about 1615 in England and probably migrated with her parents, whose names are unknown. Her first appearance in the historical record was when she married Benjamin Scott in 1642 (Benjamin was born about 1611, possibly in Scotland, and died at about the age of 51 in September 1671).

Benjamin and Margaret lived first in Braintree and then Cambridge, before moving to Rowley, Massachusetts. They had 7 children together, but at a time when infant mortality was extremely high, only 3 survived to adulthood. We are descended through their daughter Mary Scott. When Benjamin died, he left Margaret with almost no resources or money (just 67 pounds and 11 shillings) and it wasn’t long before she found herself reduced to begging, just to survive, a position that would have made her very unpopular and disliked in the town. In 1692, Margaret’s status as a long-time, poverty-stricken widow and the mother of several children who had died in infancy made her a prime target for accusations of witchcraft.

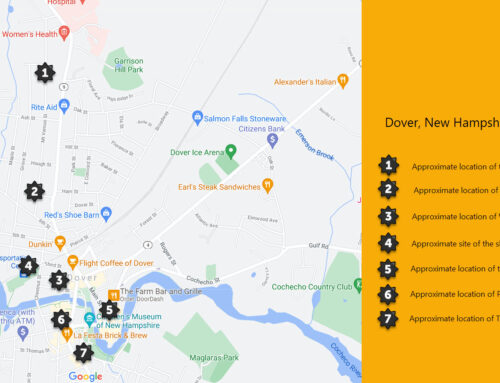

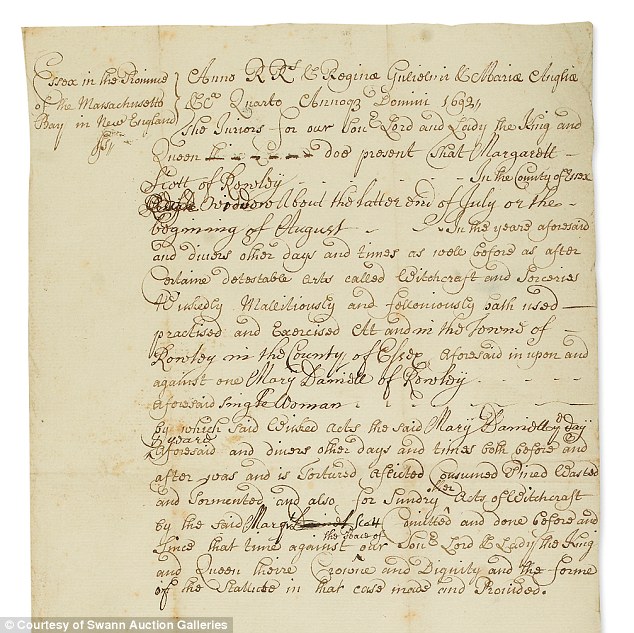

At the time of the trials, Margaret Scott lived in Rowley and was the only person from that town accused and executed. She was first examined on August 5 and had probably been arrested the day before this. Reverend John Hale, my friend’s X-time great grandfather, took notes during the examination. Spectral evidence was accepted and she was accused of turning invisible and tormenting members of the Wicomb and Nelson families, both prominent families in the town.

Her trial took place on September 15. Some of the testimony against her are clear examples of what historians call “refusal guilt syndrome.” In other words, the testimony was from townspeople who had turned Margaret away when she came begging, then claimed that bad things happened to them after this. They blamed their bad fortune on the witchery Margaret cast against them. Margaret’s specter was also accused on tormenting Frances Wicomb, and Ann Putnam and Mary Warren claimed to have witnessed this.

Margaret maintained her innocence throughout her trial and execution. She was in the last group to be executed, and shortly after this, the many others who had been jailed were released. When all eight of those accused and hanged that day were dead, Reverend Nicholas Noyes was quoted as saying, “What a sad thing it is to see eight firebrands of Hell hanging there.”

More than three centuries later, on October 31, 2001, Margaret was officially exonerated. Most of the executed had been exonerated in the early 1700’s, but for reasons unknown, Margaret’s family didn’t come forward at this time.

There is a memorial to Margaret that was erected in 1992 at the intersection of Main Street (Route 1A) and Pleasant Street in Rowley. There is also a restored historical home built in 1676 by Margaret’s son Benjamin. It is not known where Margaret lived in 1692, but it is possible she could have been living with her son.

In March 2012, Margaret’s original indictment was sold at a New York auction for $26,000. It was the first Salem witch trial document to be sold in 30 years. it was auctioned again in 2017 for $137,000.

Other Witchcraft-Related Genealogical Discoveries

These stories of the Salem Witch Trials were not the only ancestors connected in various ways to accusations and at times, executions, for witchcraft.

Anther ancestor, Jacquetta of Luxembourg, born about 1415 and lived until 30 May 1472, deserves and will have a blog post dedicated to her in the future. My 17th great-grandmother on my paternal side, Jacquetta was an amazing woman who played a pivotal role in the War of the Roses. Known best as the mother of Queen Elizabeth (from whom we are descended) who was the wife of King Edward IV (we are NOT descended from Edward, but rather from Elizabeth’s first husband Sir John Grey who was killed in battle leaving her a young widow, and their oldest son Thomas), Jacquetta was also accused, imprisoned, and brought to trial for witchcraft during the brief period when her son-in-law Edward was ousted from the thrown in 1469 during a battle associated with what has come to be known as the War of the Roses. When Edward regained the throne, he released her and dismissed all the charges against his mother-in-law, Jacquetta. I’m currently researching and tell Jacquetta’s story in full in a future blog post.