Karma moves in two directions. If we act virtuously, the seed we plant will result in happiness. If we act non-virtuously, suffering results.

— Saying Lipham

It is doubtful that our ancestor Elizabeth Heard (born Elizabeth Hull in 1628 in Devon, England, daughter of Rev. Joseph Hull), was thinking of Karma on that fateful early September day in 1676 when she saved the young boy’s life.

While cool at night, with a crisp edge to the air, days are still warm in the Seacoast region of New Hampshire in early September and the leaves on the maples and oaks in the forests surrounding the young settlement of Dover, founded in 1623, would have been just beginning to show tinges of the oranges, golds, and reds that would blaze within a few weeks.

As King Philip’s War began to wind down, hundreds of Wampanoag’s had fled the Massachusetts’ forces that summer and were sheltering temporarily with the local Pennacook-Abenaki tribe living in the area surrounding Dover. The Pennacook’s maintained a relatively friendly trade relationship with Major Richard Waldron (aka Walderne) and other English settlers. In fact, during King Philip’s War, the peace-loving Chief Wonalancet chose to remain neutral, keeping his tribe away from the warfare and even signing a peace treaty with Waldron.

That’s why, when Waldron received orders from Massachusetts that he was to round up all local Indians and deliver them to Boston, he faced a dilemma. If he complied, it would hurt him financially. It might also harm the entire settlement, not just financially but by bringing an end to the peaceful co-existence the colonists had enjoyed with the natives for the prior five decades. On the other hand, if he refused the orders, he would damage relations with the Massachusetts Bay Colony and government.

Waldron believed he had come up with a clever solution when he invited all the native populations in the area to meet in Dover on September 7, 1676 and take part in a sham battle — essentially what was “sold” to the natives as a day of friendly, competitive war games. Oblivious to the deceit, nearly 400 showed up that morning, excited for what promised to be a fun day. Approximately half were the local Pennacooks known to the Dover settlers and the other half Wampanoags from Massachusetts.

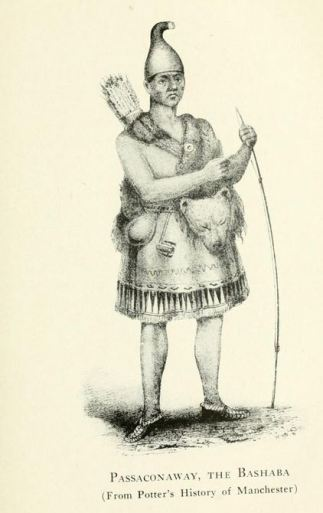

19th century reconstruction of Passaconaway, 17th century sachem of the Penacook of New Hampshire; father of Chief Wonalancet; Chandler Potter’s “History of Manchester” 1856, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Despite the raucous war games happening approximately a half-mile away, it was likely a quiet early afternoon at the Heard home where Elizabeth, now 48 years old, lived with her husband John and their seven youngest children who were still unmarried and living at home.

But as Waldron’s plans, aided by Major Charles Frost, were put into motion, it became clear to all in attendance that his invitation was anything but neighborly and benevolent. The day had been planned as trickery, and an easy way to separate and round up all of the unfamiliar, non-local Indians–more than 200 of them according to historical accounts.

While they couldn’t know at the time what was to be their ultimate fate, the Massachusetts Indians captured that day were sent back to Boston where a number of them were hanged and the remainder were sold into slavery. But in the moment, all they knew was that they had been betrayed and that the outcome was not likely to be in their favor. The war game competitors scattered and the games quickly devolved into a scene of chaos.

One of the major doctrines of Puritanism in 17th century Colonial America was predestination. That is, God will decide who is saved or damned. What you do during your daily life makes zero difference. There was no need to even think about it; Elizabeth, a devout Puritan raised by a father who was a Puritan minister, would have known in her heart that her destiny was absolutely predetermined.

But that heartfelt certainty about predestination wasn’t enough to stop the fated actions that warm, late summer day, leading to unmistakable karmic justice playing out just 12 years later.

How people treat you is their karma; how you react is yours.

— Wayne W. Dyer

In the chaos of the day, as the games broke up and the participants scattered in all directions, Elizabeth began to hear cries of angry betrayal ringing in the distance mingled with the panicked cries of mothers separated from their young children during the rounding up.

A mother of 12 herself, six boys (the youngest only eight that year) and six daughters (one who had died as an infant), when she saw the young Indian boy trying to hide himself in the stand of oaks near her home, pure terror on his face, fearing for his life, it is easy to imagine that maternal instinct kicked in. She didn’t even stop to question her instincts, never mind concern herself with the karmic consequences of what she was about to do. Rushing him into her home, she hid him for the rest of the day and into the early evening until the chaos had died down and she believed it was safe enough to send him on his way.

For Elizabeth, this was an event that was quickly forgotten in the busy schedule of endless childcare, gardening, and household chores that filled her every day in Colonial America. The young boy, on the other hand, convinced that she had saved his life, NEVER forgot the kindness and humanity she had shown him that day.

In her wildest dreams, Elizabeth would never even imagine that the gratitude from that event would eventually save her life.

Twelve years later, in June of 1689, Elizabeth, widowed just six months earlier, traveled with three of her grown sons, a daughter, and grandchildren, on a boat that might have been one of the earliest gundalows (a ship made specifically for the shallow rivers that criss-cross southern New Hampshire), navigating the river more than ten miles to Portsmouth to trade for supplies.

In the twelve years that had passed since the day of the sham battle, tensions had mounted and the relationship between the Penacook Indians and the Dover settlers became increasingly strained. Chief Kancamagus had replaced the peace-minded Chief Wonalancet, and Kancamagus wanted revenge for the injustices dealt by the settlers to his people, not the least of which was the never-forgotten betrayal of his people by Waldron, during the sham battle.

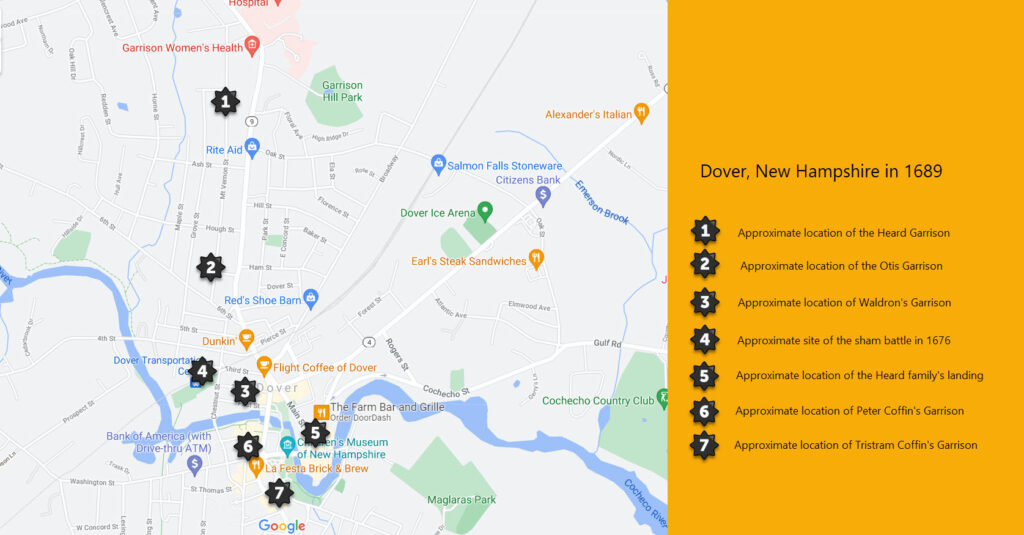

Aware of the growing threat, the settlers in Dover fortified and garrisoned five homes at public expense, each chosen because of its strategic placement. The home of John and Elizabeth Heard located on the north side of the river was among these, located near what is now known as Garrison Hill. The others belonged to Richard Waldron and Richard Otis, also on the north side of the river and the home of Peter Coffin and his son Tristam Coffin’s home, both on the south side.

At night, the neighboring families would gather and take refuge in these garrison homes built with foot-thick walls and surrounded by eight-foot fences made of logs set upright in the ground.

On the tragic evening of June 27, 1689, Governor Simon Bradstreet (also an ancestor – 11th great grandfather) in Boston had been alerted to the danger, and the letter he sent just that day, warning Major Richard Waldron of the threat, was enroute. Unfortunately, the warning didn’t make it in time.

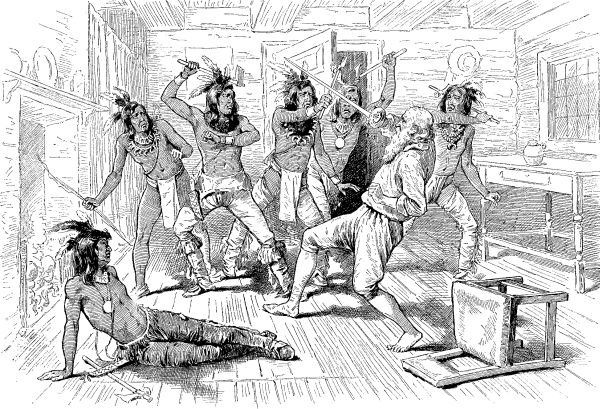

The death of Major Waldron; By Artist Unknown – OLD TIMES IN THE COLONIES. BY CHARLES CARLETON COFFIN. No. I. HOW THE INDIANS WERE WRONGED, AND THEIR REVENGE, from: Harper’s Young People, June 29, 1880 An Illustrated Weekly p.496, Public Domain

In what had become a common practice, especially on cool evenings, two Pennacook squaws asked for entry and were allowed to sleep near the kitchen hearth of each of the five garrisoned homes. Just before dawn, in each garrison, the squaws opened the doors and gave a long whistle.

Elder William Wentworth (another ancestor – 9th great grandfather) was asleep in the Heard garrison, watching over it while Elizabeth and her family were away. The barking of dogs in response to that whistle woke Wentworth, age 71 at the time, who rushed to the door and was able to slam it shut just as the marauding Pennacooks were entering. While bullets were shot through the door over his head, Wentworth threw himself against the door and somehow managed to keep it barred against the attackers. The Heard garrison was the only one spared in the raid that day.

In the Waldron garrison, Major Waldron who was 74 years old by that time, was dealt his own karmic justice. Waldron was brutally tortured and killed while his family watched in horror and then were killed or taken captive themselves and the garrison burned. The Coffin families who had maintained friendly relations with the Indians escaped with their lives, although their homes were both looted. The Otis garrison was burned and Richard Otis was killed, along with a son and daughter. His wife, an infant daughter, and two grandchildren were taken captive to Canada.

Most Gods throw dice, but Fate plays chess, and you don’t find out until too late that he’s been playing with two queens all along.

–Terry Pratchett

Returning from a day of trading in Portsmouth at exactly the time the massacre was reaching its crescendo, Elizabeth and her family were completely unaware of the danger until, close to docking, they smelled smoke and heard the war whoops and screams coming from the village. Terrified, they quickly ran the boat ashore near the Waldron garrison and were horrified at the carnage they found.

Their presence still undetected by the warriors, Elizabeth fainted from her fear and when she was aroused, insisted that she could go no further. She pleaded with her family to go ahead without her and to save themselves. Fearing for their own lives and the lives of their children with them, when Elizabeth promised to remain hidden in the bushes until it was safe to emerge, they agreed and continued on to the Heard garrison; all except for Elizabeth’s daughter Mary and her husband John Ham (from whom we are also descended) who instead turned their boat around and returned to Portsmouth to give the alarm, fearing that Portsmouth would be next.

With daylight approaching, Elizabeth broke her promise and made her way silently and stealthily from thicket to thicket, back in the direction of her home which she expected would be burned to the ground. But, not stealthily enough as she was spotted by one of the attacking warriors who rushed toward her twice, each time pointing his pistol at her head, staring hard at her, and then running away.

Every act done, no matter how insignificant, will eventually return to the doer with equal impact. Good will be returned with good; evil with evil.

— Nishan Panwar

In a remarkable twist, that warrior who spared her life was the young boy, now grown, that Elizabeth had saved 12 years before. He had never forgotten her kindness and chose to repay it that day.

When the Indians left the settlement, Elizabeth returned to find her home and family safe from the tragedy that had befallen her neighbors.

In total, besides the garrisons, five or six other homes were burned, 23 of the English settlers were killed, and another 29 were taken captive; in all, about 25% of the total population of the settlement. Other ancestors who were killed in the raid include William Horne (10th great grandfather) and also (possibly, some parts of the lineage is still undocumented) Mary Ann (Paul) Hanson (10th great grandmother) and her sons Joseph and Benjamin and daughter-in-law Elizabeth Boyce.

While it has been said that it was the raid that June day of 1689 that ended 50 years of peaceful co-existence between the natives and colonists, in truth that end likely came 12 years earlier, with Waldron’s war games scheme. Over the next half-century, similar attacks were made in neighboring settlements including Durham, Exeter, Salmon Falls, Rochester, Eliot, and York, among others.

By 1770, to the relief of the colonists, the attacks had ended. Unfortunately, the end of the violence was not because peace had finally come to the region. Rather, the native population was completely decimated by then, driven out by the European colonists or dead from diseases brought from Europe, ending their long dominance in the region.

Genealogical Tidbits

Elizabeth Hull, 10th great-grandmother three times over, was born in 1628 in Northleigh, Devon, England, the daughter of Reverend Joseph Hull (b. April 25, 1594 – d. November 19, 1665) and his wife Joanne. Elizabeth immigrated with her parents, arriving on the ship Marygold in Boston, on May 6, 1635 when she was just seven years old.

In 1643, in York, Maine, Elizabeth married John Heard. John was born on November 29, 1612 in Chichester, Sussex, England. It is believed that he immigrated to Boston in 1639, living first in the Kittery and York area of Maine, before he and Elizabeth moved to Dover in about 1655. He worked in the shipping and ship building trades.

Together John and Elizabeth had 12 children.

We are directly descended through three daughters (Mary, Elizabeth, and Dorcas)

Benjamin (b. February 20, 1643 – d. February 1710)

Catherine (b. 1646 and died as an infant)

Mary – our ancestor (b. January 26, 1649 – d. December 9, 1706)

Abigail (b. August 2, 1651 – d. December 7, 1706)

Elizabeth – another ancestor (b. September 15, 1653 – d. November 11, 1705)

Hannah (b. November 25, 1655 – d. October 7, 1687)

John (b. February 24, 1658 – d. 1733)

Joseph (b. January 4, 1660 – d. before 1687)

Samuel (b. August 4, 1663 – d. October 2, 1697)

Dorcas – another ancestor (b. 1665 – d. about 1707)

Tristram (b. March 1, 1666 – d. April 18, 1734)

Nathaniel (b. September 20, 1668 – d. April 3, 1700)

John Heard died on January 17, 1689 (or possibly 1688). Elizabeth lived in her garrison house for the remainder of her days and died November 30, 1706. Pike’s Journal notes “Old Widow Heard deceased after a short illness with fever. She was a grave and pious woman, even the mother of virtue and piety.”

Cotton Mather's Account of the Event

As published in Cotton Mather’s Magnalia Christi Americana

“Mrs. Elizabeth Heard, a Widow of a Good Estate, a Mother of many Children, and a Daughter of Mr. Hull, a Reverend Minister formerly Living at Piscataqua, now lived at Quochecho. Happening to be at Portsmouth, on the Day before Quochecho was cut off, She Returned thither in the Night, with one Daughter and Three Sons, all masters of Families. When they came near Quochecho, they were astonished, with a prodigious Noise of Indians, Howling, Shooting, Shouting, and Roaring, according to their manner in making an Assault. Their Distress for their Families carried them still further up the River, till they Secretly and Silently passed by some Numbers of the Raging Salvages. They Landed about an Hundred Rods from Major Waldern’s Garrison; and running up the Hill, they saw many Lights in the Windows of the Garrison, which they concluded the English within had set up, for the Direction of those who might seek Refuge there. Coming to the Gate, they desired entrance; which not being readily granted, they called Earnestly, and bounced, and knocked, and cried out of their unkindness within, that they would not open to them in this Extremity. No Answer being yet made, they began to doubt, whether all was well; and one of the young men then climbing up the wall, saw a horrible Tawny in the Entry, with a Gun in his Hand. A grievous Consternation Seiz’d now upon them; and Mrs. Heard sitting down without the Gate, through Despair and Faintness, unable to Stir any further, charged her Children to Shift for themselves, for She must unavoidably There End her Days. They finding it impossible to carry her with them, with heavy hearts forsook her; but then coming better to herself, she fled and hid among the Barberry-bushes in the Garden: and then hastning from thence, because the Day-Light advanced, She sheltered herself (though seen by Two of the Indians) in a Thicket of other Bushes, about Thirty Rods from the House. Here she had not been long, before an Indian came towards her, with a Pistol in his Hand: the Fellow came up to her, stared her in the Face, but said nothing to her, nor she to him. He went a little way back, and came again, and Stared at her as before, but said nothing; whereupon she asked what he would have? He still said nothing, but went away to the House Co-hooping, and Returned unto her no more. Being thus unaccountably preserved, She made several Essays to pass the River; but found herself unable to do it; and finding all places on that side the River filled with Blood, and Fire, and hideous Outcries, thereupon she Returned to her old bush, and there poured out her ardent Prayers to God for help in this Distress. She continued in the Bush, until the Garrison was Burnt, and the Enemy was gone; and then she Stole along by the River side, until she came to a Boom, where she passed over. Many sad Effects of Cruelty she Saw left by the Indians in her way; until arriving at Captain Gerish’s Garrison, she there found a Refuge from the Storm; and here she soon had the Satisfaction to understand, that her own Garrison, though one of the first that was assaulted, had been bravely Defended and maintained against the Adversary. This Gentlewoman’s Garrison was the most Extream Frontier of the Province, and more Obnoxious than any other, and more uncapable of Relief; nevertheless, by her presence and courage, it held out all the War, even for Ten Years together; and the Persons in it have Enjoy’d very Eminent preservations. The Garrison had been deserted, if She had accepted Offers that were made her by her Friends, of Living in more safety at Portsmouth; which would have been a Damage to the Town and Land: but by her Encouragement this Post was thus kept: and She is yet Living in much Esteem among her Neighbours.”