Jacques Jahan dit Laviolette, Michelle’s 8th great grandfather is our Laviolette immigrant ancestor. He was born between 1629 and 1636 (probably 12 June 1629)in Blois, France. More specifically, he was born in the parish of Sainte-Solemne (today this is the parish of Saint-Louis) in Blois (diocese of Chartres), Orleanais, France.

Blois is in central France, situated on the banks of the lower river Loire between Orleans and Tours.

Blois is in central France, situated on the banks of the lower river Loire between Orleans and Tours.

Jacques was the son of Sebastien Jahan (b. 19 Jan 1606 and d. 2 Nov. 1636) and Jeanne Oudinet or Audinet (b. in approximately 1604 and d. after 1636)

Dit names complicate research and confuse many people conducting French Canadian genealogical research. The name Laviolette is what is known as a secondary surname. Jahan was the original surname of our family. These secondary names (dit names) were similar to a nickname and helped differentiate different branches of the same family. The military also used dit names similar to the way we use identification numbers today. We know that Laviolette was a dit name given to soldiers in feudal France, so it is likely that Sebastian had been a soldier and his dit name was passed down to his son.

The landscape through the river and Blois, France, reflects the old city in the Loire.

Streets of the medieval city of Blois

It wasn’t until the mid-1700s that our family fully adopted the surname Laviolette. The children of Jean Baptiste Jahan dit Laviolette b. 10 Apr 1730 and Therese Arsenault b. 12 Oct 1732, who married in 1759, were the first that I have found baptized Laviolette.

Records have shown that Sebastien was a tanner in France and we know for certain that this was the trade of Jacques in Canada, so it is likely that the trade was passed down to him. But it is not likely that Sebastian taught him the trade since Jacques was just 7 years old (or younger) when his father died. There is no record of Jacques’ mothers death, although we do know she was still living in 1636 when her husband died.

Jacques first appears in the historical records of New France on 29 May 1656, when he made a written agreement with a Mr. Quentin Moral from Trois- Rivieres. Quentin Moral was a seigneur, essentially a feudal lord over parcels of land that he rented to settlers. Many of the young men who went to Canada did so thinking that it would be a temporary work arrangement and planned to return to France at the end of their contract. Approximately 2/3 did return home as planned, but the remaining 1/3 chose to stay, marry and raise families in Canada.

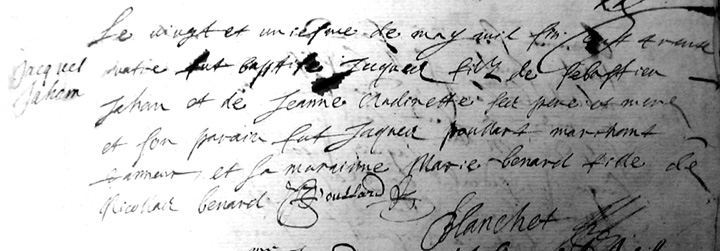

Jacques baptismal record from Sainte-Solene, Blois, France

The date of arrival in 1656 (or before) designates Jacques as one of the first settlers of Quebec—a true pioneer. While Quebec City had been founded by Samuel de Champlain in 1608, by 1650 there were only 30 homes in the city and by 1663 just over 100 homes, with a population of about 500 people. It was during this decade of growth that Jacques and his future wife Marie Ferra independently left their homes and families in France for the dangerous unknown of New France.

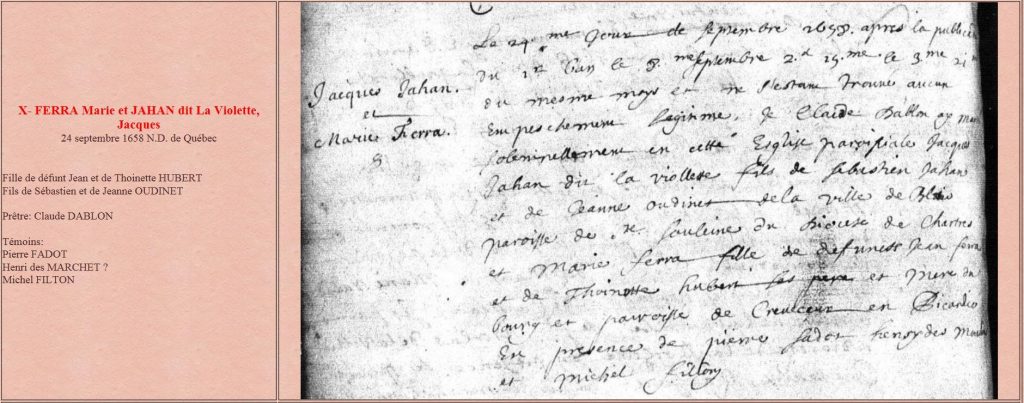

Jacques married Marie Ferra On 24 September 1658 in Quebec City. It is not known if Marie was able to sign the marriage contract which was drawn up 07 September by notary Peuvret in the home of Sieur François Bissot, but Jacques did sign it himself, indicating that he may have been literate. The fact that the contract was signed in Bissot’s home suggests that Marie lodged with him prior to her marriage.

Marie Ferra was born about 1638 in Crève-coeur-le-Grand (near the diocese of Beauvais), Picardy, the daughter of Jean Ferra (1603 – 1677) and Antoinette Hubert (1603 – 1682).

We may never know exactly why, except for the promise of a better life in which she had the right, unlike in France, to choose her spouse and future, but in 1658, Marie left made the trip to Canada. She is known as a “Filles a Marier” (meaning before the King’s Daughters). This is a phrase that refers to marriageable girls who immigrated—usually alone or in small groups–to New France between 1634 and September 1663 seeking a better life. There are 262 known “Filles a Marier” in total. These young women weren’t recruited or sponsored in any way by the government, like the later “Filles du Roi” women were, although some were recruited by private merchants and religious groups hoping to entice the young male colonists to remain in Canada, marry, and populate New France rather than return to France.

We may never know exactly why, except for the promise of a better life in which she had the right, unlike in France, to choose her spouse and future, but in 1658, Marie left made the trip to Canada. She is known as a “Filles a Marier” (meaning before the King’s Daughters). This is a phrase that refers to marriageable girls who immigrated—usually alone or in small groups–to New France between 1634 and September 1663 seeking a better life. There are 262 known “Filles a Marier” in total. These young women weren’t recruited or sponsored in any way by the government, like the later “Filles du Roi” women were, although some were recruited by private merchants and religious groups hoping to entice the young male colonists to remain in Canada, marry, and populate New France rather than return to France.

The courage that it must have taken these young women to make the dangerous crossing into the wilds of New France is incredible. Not only was the trip from France to Canada extremely dangerous, with approximately 10% dying en route, mostly from sickness and disease, but they were going to a place that in France had a reputation as being “savage” and a “place of horror.” The promise of a better life in Canada than they were living in France must have had a remarkable draw to gamble their lives as they did.

Nine ships arrived carrying Filles a Marier in 1658, carrying a total of 27 young girls and women. Of these, 14 went on to Montreal and 13 remained in Quebec City. Based on the date of Jacques and Marie’s marriage contract, she likely arrived on an unknown ship on 11 July, on the Taureau (150 tons captained by Elie Tadourneau) on 6 Aug, or on the Nouvelle-Hollande on 15 August.

Those first couple of years in Quebec City were likely perilous ones for the newly married couple. By 1660, immigration had slowed dramatically because of fear from attack of the Iroquois during what was known as the Beaver Wars (aka Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars). The Beaver Wars are generally recognized as encompassing most of the 17th century but hostilities had really increased in 1659/60. The real danger to the inhabitants of Quebec City was small, but it’s been reported that there was great fear among the settlers during these years.

Jacques was a tanner, but also made a living as a farmer. On 22 March 1660 he obtained official title to land of two acres frontage along the coast of Beaupre called Les Chesnes from Guillaume Couillard.

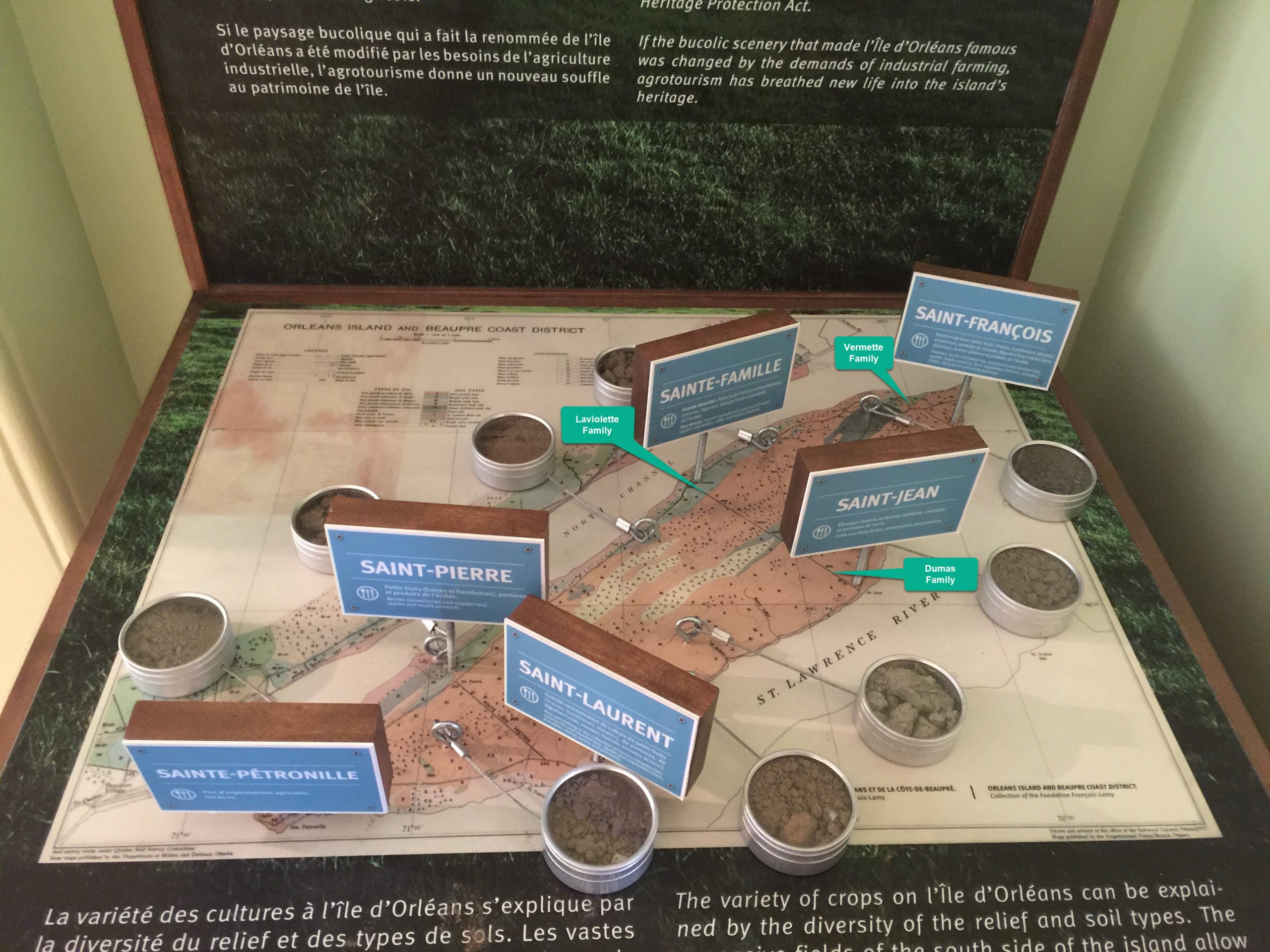

He also received a grant of land on the Ile-d’Orleans from Sieur Charles de Lauzon and this is where he and Marie made their home, in the first settlement of Sainte-Famille, founded in 1661. Once again, as founding families of the island community, Jacques and Marie can be considered true pioneers. By 1668, the island had a population of 471 people and construction of the first church began in 1669. Until that time, their children were baptized at Chateau-Richer.

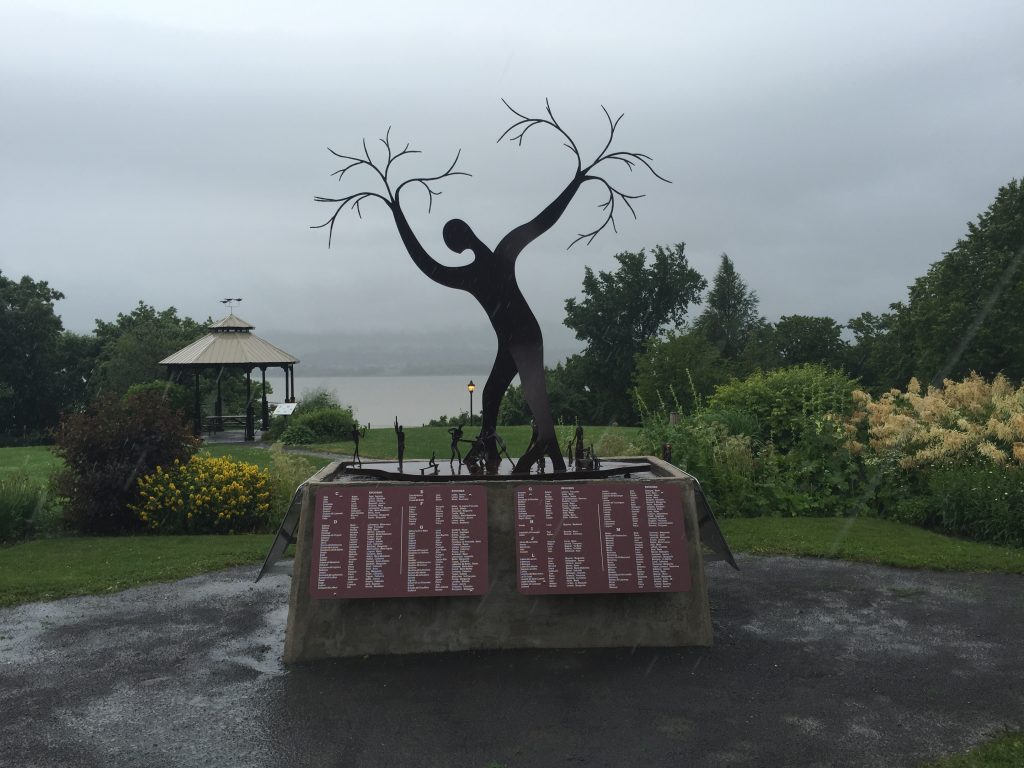

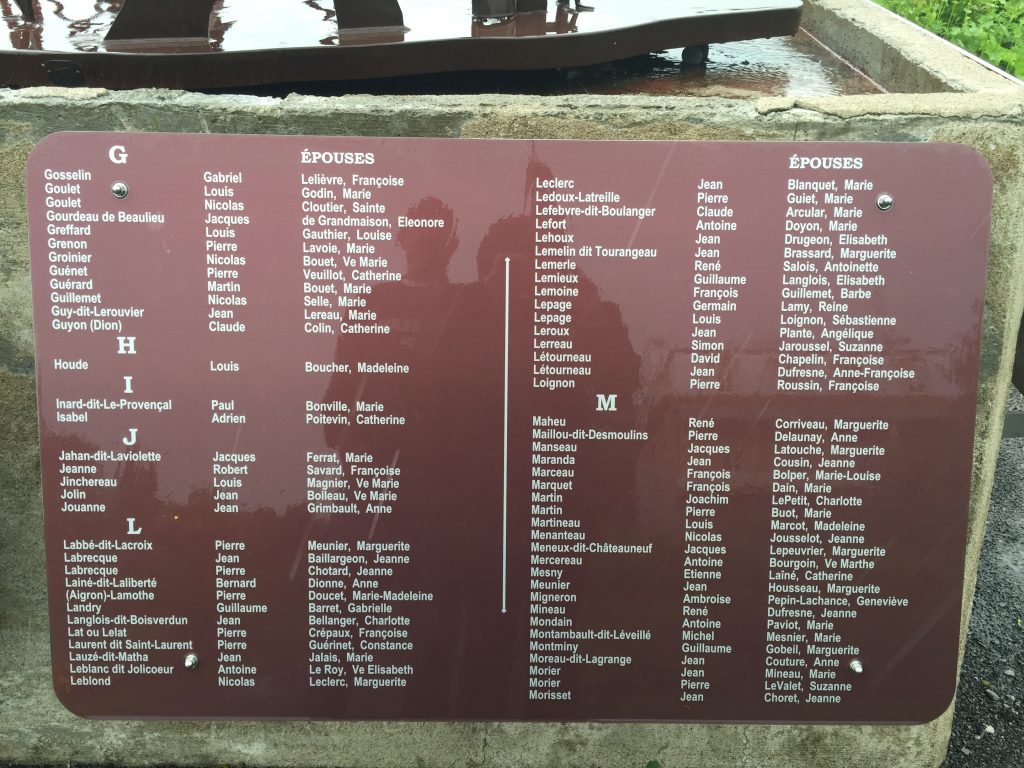

Close up of the monument on the Ile-d’Orleans honoring the founding families.

In 1676, the island was divided into Saint-Pierre, Saint-Jean, Sainte-Famille and Saint-Paul (renamed Saint-Laurent in 1698)and by 1685, the population had close to tripled to 1205 people.

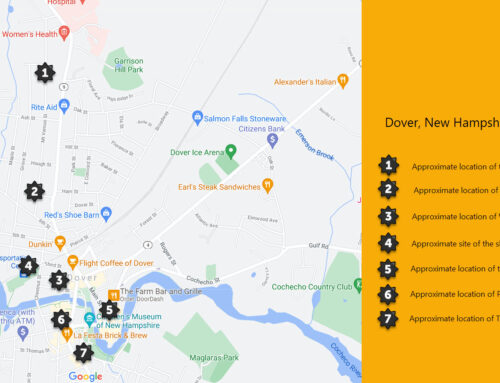

Many of our ancestors on both sides were founding families, settling the Ile-d’Orleans. This map is labeled to show the proximity of three of them, all living as neighbors in the mid-to-late 1600s: Laviolette, Dumas, and Vermette.

One of the oldest remaining houses on the island is Maison Drouin. While it was built in 1730, more than 50 years after Jacques and Marie settled there, it provides a glimpse into what their home may have looked like and how they lived.

Modern photo of Sainte-Famille. Paul Paradis / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)

In 1666/67, Jacques declared that he had 15 acres of land and a single “horned animal.” Life on the island was harsh and Jacques would have had to farm in order to survive, in addition to working in a trade, which we know was “tanning” for him.

Jacques was listed in the 1681 Ile d’Orléans census as a 50 year old master tanner (this is likely the source of the 1631 birth year often cited on the internet). Tanners at the time prepared the skin of animals to produce leather. Tanning was a smelly trade and was most commonly a trade of the “poor” people done on the outskirts of town.

Tanning would have been an exhausting trade. The wet, water-soaked hides would have been exhausting to handle. There were a lot of steps to the tanning process. First soaking the hides in lime, to burn off hair and flesh, the skins were then washed in chicken droppings that had been diluted in water to neutralize the lime. The hides were then soaked in tannin baths for several months. In Canada, this tannin bath would have been made by hemlock or spruce bark. Finally, the leather was stretched, covered in oil, and then hung to dry. In total, this was at least a 4 month process.

In that same 1681 census Jacques declared owning a rifle, 10 horned animals, and 25 acres in land.

On 3 February 1683, he began a nine-year partnership with his neighbor Hypolite Thivierge to start a tannery on the Ile d’Orleans. The tanning mill was located on the land of Thivierge and Jacques was to supply the leathers.

The business endeavor apparently did well as evidenced by a number of land transactions made by Jacques in the years that followed.

Jacques and Marie had 11 children together. Sadly, only 4 lived to adulthood and only 3 outlived Marie. It is difficult, almost impossible, to imagine the heartbreak of losing 8 children. While this was common in the 17th century, the grief one would feel at losing a child is no less than it would be in modern days.

(f) Louise Jahan dit Laviolette b. 06 Oct 1661 d. 10 Oct 1661 – Died as an infant

(m) Jacques Jahan dit Laviolette b. 24 or 28 Feb or Nov 1663 – d. 16 Apr 1711 – our ancestor

(m) Jean Jahan dit Laviolette b. 22 May 1665 – d. 19 Mar 1666 Died at 10 months old

(f) Marie Jahan dit Laviolette b. 08 Feb 1666 – d. Abt 1719

(f) Elisabeth-Marie Jahan dit Laviolette b. 20 Jan 1669 – 21 Apr 1670 Died at 4 months old

(m) Hippolyte Jahan dit Laviolette b. 16 Mar 1671 – d. Abt 1689 Died at 18 yrs

(f) Jeanne Jahan dit Laviolette b. 07 Oct 1673 – d. Abt 1689 Died at 16 yrs

(f) Catherine Soeur Sainte Croix Jahan dit Laviolette b. 30 Jan 1676 – d. 21 Apr 1734

(f) Elisabeth Jahan dit Laviolette b. 03 Dec 1678 – d. 18 Oct 1750

(m) François Jahan dit Laviolette b. 14 Jun 1682 – d. 05 May 1699 Died at 17 yrs

(f) Geneviève Jahan dit Laviolette b. 31 May 1684 – d. Abt 1687 Died at 3 yrs

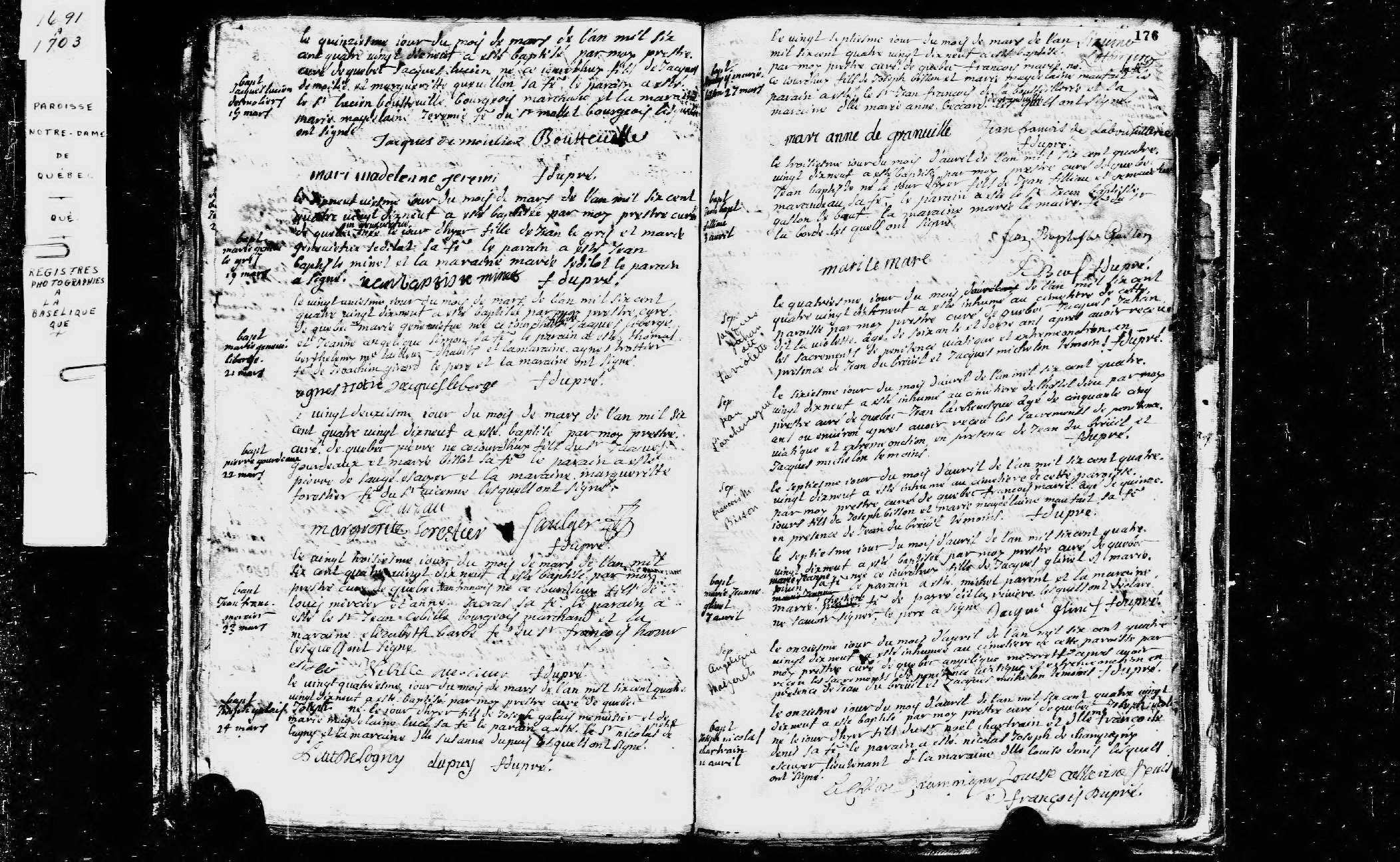

Jacques died 04 Apr 1699 at the age of 70.

Jacques Jahan dit Laviolette death record in 1699.

On May 5th, one month after Marie buried her husband, she buried her son François at Sainte Famille. Both may have been the victims of an unidentified epidemic that struck the colony that year.

Marie Ferra died at age 75 and was buried 17 February 1713 at Saint-Jean, Ile d’Orléans.